As an Evangelical Protestant, few things provoked me to debate more than the Marian Dogmas. The notion of a ‘dogma’ itself was suspect. But doubling down on what I considered unjustifiable claims by declaring them infallibly true was worse by an order of magnitude.

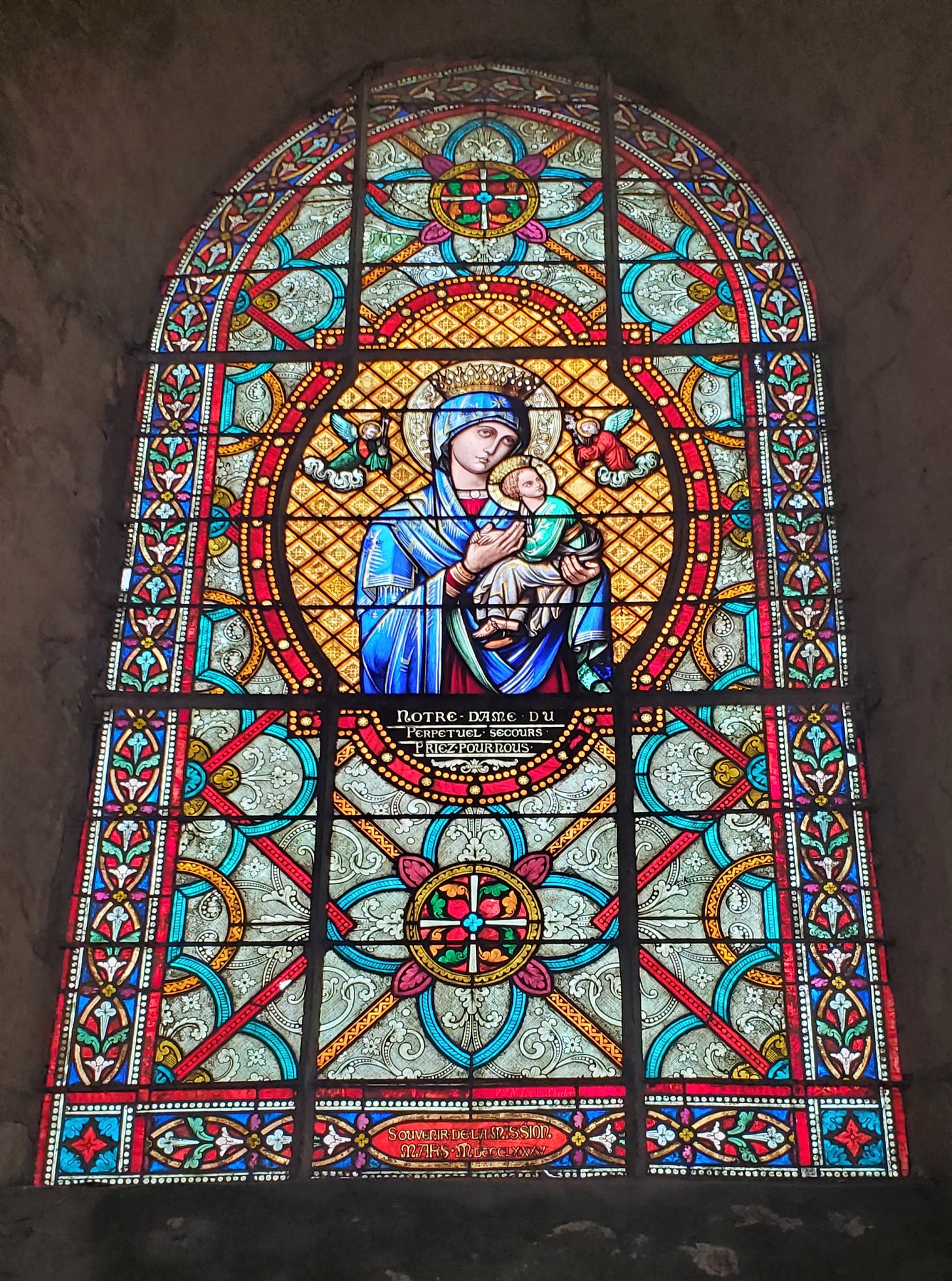

I relished every opportunity to show Catholics how foolish it was to assert that Mary was without sin, perpetually virgin, assumed body and soul into heaven, and is properly called “Mother of God.” Ultimately, the last of these was the first to break through the dam of my recalcitrance, Since we are approaching the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God, I would like to share what caused me to change my mind about this essential element of the faith.

Sometime around fourth grade, we learn about figures of speech. We hear about simile, metaphor, hyperbole, onomatopoeia, and idiom. Idioms were the most interesting to me. Still are. When using an idiom, the phrase's meaning cannot be understood from the words. For example, we might “spill the beans” to reveal a secret or say “piece of cake” to indicate that something is easy to do. A person learning English is understandably befuddled by these phrases. I think there may be an old I Love Lucy episode touching on this very theme.

In any event, with idioms, further explanation or context is always needed to understand what the author or speaker is communicating. Theological language often works this way. Idioms form an important and overlooked aspect of the Christian faith. Specifically, the communicatio idiomatum (communication of idioms) is a concept that Catholics hold quite dear.

Think about the common argument Catholics make for Mary being called the Mother of God. It usually goes something like this. “Since Jesus Christ is God and Mary is the Mother of Jesus, it follows that Mary is the Mother of God.” The Protestant interlocutor will find the argument misleading or trading on an equivocation; to them saying that God is born implies He has a beginning, which is absurd. The Protestant might then argue that the divine nature of Christ was not born, but the human nature of Christ came to be at the Incarnation and we ought not deflect focus from Jesus to Mary. The Catholic answer here is that persons are born, not natures. At this point, the Protestant likely thinks the Catholic is confused, and vice versa. But such confusion might have been avoided if the communicatio idomatum had been the point of departure.

Most Protestants maintain the orthodox view of Jesus Christ as truly God and truly man. Vera Deus, vera homo, as the old formula goes. Like Catholics, Protestants believe Christ is one Person with a divine and a human nature. The Reformation did not explicitly repudiate any of the Christological formulations of Nicaea, Constantinople, or Chalcedon. This may be evidenced by the fact that Protestant churches often recite the Creed or implicitly affirm what it says in their various statements of faith. This is a key piece of common ground because Catholic Dogmas about Mary are essentially Christological. They all pertain to the mystery of the Incarnation of the Lord. For instance, the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary is a direct corollary of Jesus being truly man and born without Original Sin.

In technical language, the hypostatic union refers to the two natures of Christ, divine and human, subsisting in one Person. Accordingly, we say the Person of Christ is fully divine and fully human. The communication of idioms informs us what we say about the Lord Jesus in concrete terms must be said about the Person. We must speak of the Person in His entirety, without separating, confusing, or mixing His natures.

All orthodox Christians agree Jesus died on the Cross at Calvary. All orthodox Christians also agree God cannot die. There is further agreement that Jesus is God and man. Yet we cannot say the human nature of Jesus died on the Cross and the divine nature did not. This would be to deny the union of the natures. We must instead say that Christ suffered and died on the Cross. This does not entail being able to say “God suffers.” It would be wrong to say God as God changes or undergoes suffering, which is what would follow if we said something like “God dies on the Cross.” It would also be wrong to say that Jesus Christ did not die. The mystery of the Incarnation means we must affirm the Incarnate Lord Jesus Christ died on the Cross and subsequently rose again.

Returning to the Dogma of Mary’s Divine Motherhood, we can see where the communication of idioms comes into play. The claim “Mary is the Mother of God” does not stand alone. Idioms do not work that way. Words in the phrase alone do not bring it full justice. What Catholics mean is that Mary is the Mother of the Incarnate Lord Jesus. The Incarnate Lord Jesus is truly God and truly man. Since she bore He who is God and man, it is proper to call her the Mother of God. This is because the actual meaning of the words communicates something beyond the mere words themselves. Again, what is said about the Person of Christ is to be said of the Person in His entirety, whether it is a human or divine predication. We can say Christ got tired, that He suffered. We can also say Christ is eternal, omnipotent, and so forth.

The upshot is that to deny Mary is the Mother of God is to deny the communication of idioms. This denial forces one to divide the natures in Christ or reject the mystery of the Incarnation. As I briefly mentioned earlier with the example of the Immaculate Conception, a similar case could be made with the other Marian Dogmas. Ignoring the communication of idioms gives birth to a host of heresies that all Christians of goodwill must avoid. Whatever we predicate concretely of Christ must be said of His Person. Each statement we make about Jesus must respect the mystery of the Incarnation. Catholics and Protestants both seek to uphold and respect this mystery. It is precisely to this area of common real estate that I came before advancing, by God’s grace, to affirm the Dogma itself.

What first turned my attention to the communicatio as a Protestant was studying the concept of divine impassibility. To say that God is impassible is just to say that He is not acted upon from without. It is to say God does not suffer, because to suffer is to undergo. There is a concerted movement in some theological circles to normalize a suffering God. I believed, and still do, that it is impossible to predicate suffering of God. It was in the context of a formal, online, exchange with another Protestant on this topic that I was forced to dig deeper into the communicatio.

Protestants tend to appreciate the communication of idioms. For example, Apologist Matt Slick writes about the importance of it on the CARM website (1). Ligonier Ministries, a Protestant ministry, also embraces this notion and its historical importance (2). Incidentally, it was in an R.C. Sproul sermon that I was first introduced to the term Theotokos (‘God-bearer’) concerning Our Lady. For good measure, the Westminster Confession of Faith affirms the communication of idioms as well (3).

Granted, the foregoing examples are more from the Reformed tradition. That said, based on my experience as an Evangelical (Southern Baptist - non-Reformed), I believe these views would be fairly consistent across the board. The Christology affirmed by the Catholic Church is the same as most Protestant denominations. So, there is ample ground to say it is sufficiently ‘biblical’. I would then argue we find solid agreement on the necessity of the communicatio idiomatum to proper Christology. The question becomes exactly how to apply it to claims about the Lord. Selective application of the communicatio is deeply problematic because it leads to heterodoxy (wrong praise/belief). If we are faithful to Sacred Scripture, what we say about the Lord cannot ignore His Mother, given her God-ordained role in salvation history. Failing to extend the predications codified in the Marian Dogmas does injustice to the Incarnation.

Recall that the Marian Dogmas are about Christ. Ignoring them only leads to a lower view of the Incarnation. Protestants exhibiting a desire to remain within orthodoxy should be open to understanding how the communicatio informs Marian Dogmas. Catholics do well to bring this concept out into the open and utilize it for more effective dialogue.

—

https://carm.org/doctrine-and-theology/communicatio-idiomatum/.

https://www.ligonier.org/learn/devotionals/communication-attributes.

WCF 8.7

Are you holding out on us your PhD in Theology? A very beautifully laid out explanation of Our Holy Mother, Mary, using a term I’m completely unfamiliar with, which I can’t see to rewrite, and being only a week old in the Substack universe, I’m afraid I’ll never find you again. I subscribed with gusto!